Product people get excited about solving problems that make people’s lives better. On that we can all agree. It’s the approach we choose to achieve that goal where differences arise. Sometimes the differences are significant and obvious – Agile vs. Waterfall, for example. Sometimes, they seem much less so. Take user-centered design vs. human-centered design. Aren’t users of our products human? Of course they are, but there’s more to the difference than a mere distinction.

In this episode, hosts Sean and podcast newcomer Paul Gebel welcome Kim Goodwin, author, coach, consultant, and a featured keynote speaker at ITX’s 2nd annual ITXUX2019: Beyond the Pixels design conference. Kim explains that the people closest to the problems, those who confront them every day, hold the key to their solution. To apply our designs in ways that solve those problems, we need to think in terms of meeting human needs.

Maslow’s Impact on Human-Centered Design

The terms human- and user-centered design are often used interchangeably.

“When I speak of human-centered design,” Kim says, “I see it as helping people self-actualize, without getting in anybody else’s way.”

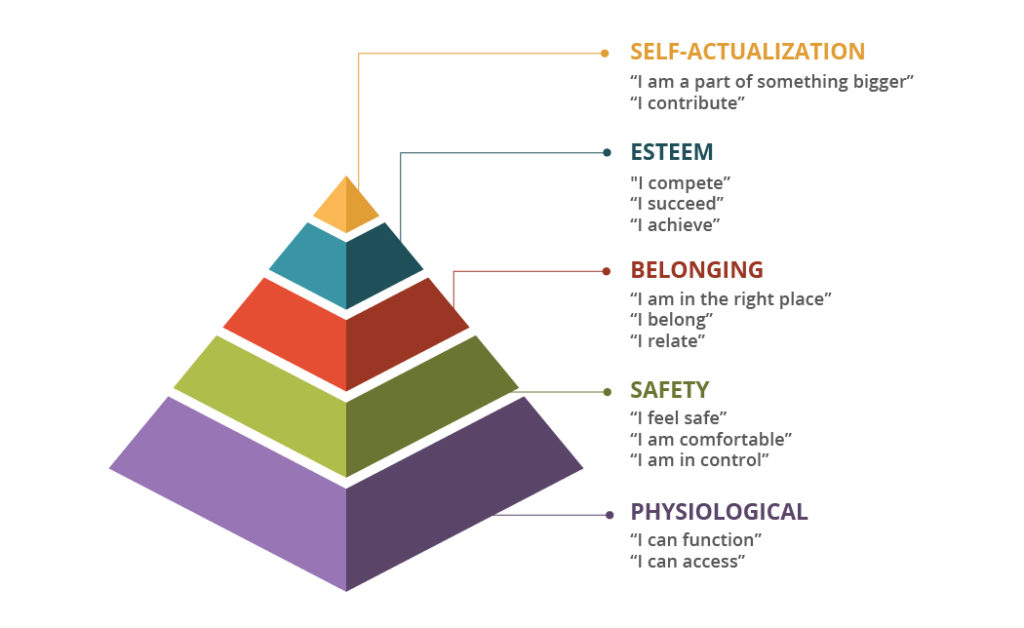

Kim’s comment hints that it’s difficult to discuss human-centered design without invoking the name, Abraham Maslow. Maslow’s work describes the range of human needs from basic physiological (“I am safe; I can function”) to self-actualization (“I contribute to something bigger than myself), and everything in between.

By delivering technology solutions that address innately human problems, designers have the power to advance users up Maslow’s hierarchy pyramid and give us a taste of the self-actualization we all crave.

Kim explains Maslow in a much simpler way; in fact, when she’s asked in social settings what kind of work she does, she responds, “I don’t even use the ‘D’ word (design). I just say, ‘I make companies better at humans. I like that because that’s really what it’s all about.”

Designers and Human-Centered Metrics

At the core of their being, designers are problem solvers, right? So, at the start of any engagement it’s important that we understand precisely what we are trying to accomplish. What’s the problem? What’s the goal? And Why?

“If we don’t ask those fundamental questions at the outset,” Kim says, “we usually end up with a misaligned team. If people respond by telling you we should build X, Y, and Z, we need to ask ‘Why? What is that going to accomplish for us and for whose benefit?’”

When we design with the goal of delivering primarily for our clients and employers, as opposed to the humans who actually use our designs, we risk targeting the wrong measures of success, Kim says. “When we over-optimize to one metric, we get distorted behavior. We get measured on the things we’re incented for…those things tend to be what’s easy to measure. What we don’t measure, though, is the impact that our products and our services have on people and on their lives,” she adds.

When we over-optimize to one metric, we get distorted behavior. We get measured on the things we’re incented for…those things tend to be what’s easy to measure. What we don’t measure, though, is the impact that our products and our services have on people and on their lives. — Kim Goodwin

The Evolution of Personas – A Hammer with No Nail

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of design work is truly knowing who we’re solving problems for. We gather demographic and psychographic data to guide our perception of the people who will benefit from our design work. These are important pieces of the puzzle, Kim offers, “but a lot of people have latched on to personas a little too much and use them like creative writing tools.

“As standalone tools, personas are not that worthwhile,” she adds. “It’s kind of like a hammer with no nail. If all you say, ‘Here’s our persona; here’s your goals,’ and proceed to tack on some fictitious details…, that may help clarify your thinking, but without a scenario your persona is not going to do much for you.” When combined with the context, personas are “hugely useful,” Kim argues.

When designers observe people in their environments and understand their technology and domain competencies, they see them in much richer detail. Designers possess the rare ability to understand how people perceive the world, as well as the tools to design experiences for that. A combination that when applied correctly draws us closer to the human-centered solution.

Designers possess the rare ability to understand how people perceive the world, as well as the tools to design experiences for that. A combination that when applied correctly draws us closer to the human-centered solution. — Kim Goodwin

When you listen to our entire podcast conversation, you’ll get to hear Kim’s answers to these and other questions:

- What’s one of the biggest mistakes that product people make when using personas?

- According to Kim, what’s only way to get a team truly aligned around what humans need?

- Why is it so important to have diverse voices on product teams?

- Which provides greater impact: technology skill? Or skill in the user’s domain?