Whether you’re building products for hundreds, thousands, or millions of individuals, design that provides as many points of access as you have users is no longer a nice-to-have. For reasons based not only in social responsibility but in sound business management, inclusive design is a must. And embedding it into our everyday ways of working begins with the designers and design teams whose duty it is to carry the banner forward.

Over the past few years, the UX design team at ITX started thinking about adopting a more inclusive lens in our work and soon came to realize why it was so important to us as designers, but also as human beings.

So in 2020, we committed 3 months to research everything that was already out there about diversity and inclusion in design. Our research culminated in the development of our Diversity and Inclusion in Design Training Guide, which includes a compilation of our favorite curated resources. This works serves as a baseline for our team to help adopt a truly inclusive design mindset.

Why product inclusion benefits everyone

Annie Jean-Baptiste, author of Building for Everyone and Head of Product Inclusion at Google, spells out that “Product Inclusion is the practice of applying an inclusive lens throughout the entire product design and development process to create better products and accelerate business growth.”

According to the University of Cambridge’s Inclusive Design Toolkit, “Every design decision has the potential to include or exclude customers. Inclusive design emphasizes the contribution that understanding user diversity makes to informing these decisions, and thus to including as many people as possible. User diversity covers variation in capabilities, needs and aspirations.”

This does not mean that one design might fit everyone, since we are acknowledging that diverse groups might require different approaches. By applying an inclusive lens to product or service development, we are intentionally trying to incorporate several points of view, needs, and differences in use to create an overall better experience that will accommodate the greatest number of people. Just like Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Toolkit states, “Designing inclusively doesn’t mean you’re making one thing for all people. You’re designing a diversity of ways for everyone to participate in an experience with a sense of belonging.”

One of the premises of inclusive design is that in addition to permanent disabilities, there are temporary and situational disabilities that might affect us all. Microsoft’s toolkit explains that “as people move throughout different environments, their abilities can also change dramatically.” For example, if you’re trying to watch a video in a noisy environment, you might benefit from closed captions – originally created for the hearing-impaired community but later used by a wider audience.

As maintained by Microsoft, “designing for inclusivity not only opens up our products and experiences to more people with a wider range of abilities. It also reflects how people really are. All humans are growing, changing, and adapting to the world around them every day.”

To summarize, in Annie’s words, “product inclusion is about thinking holistically about the dimensions that make people who they are in the moments that matter. Your customers are multifaceted, and your products must be built with that in mind.”

Therefore, one could argue that the business case for inclusive design is self-explanatory, right?

— Nicole Btesh, ITX User Experience Designer

One could even think about product inclusion as a necessary step in the design process. In her July 2016 Ted talk, artist and human rights activist Elise Roy asks, “What if we changed our mindset? What if we started designing for disability first – not the norm? As you see, when we design for disability first, we often stumble upon solutions that are not only inclusive, but also are often better than when we design for the norm.”

Shifting social norms and inclusive design

Traditionally, diversity and inclusion (D&I) has been seen as the responsibility of the Human Resources department, with a focus on the hiring process and talent development, rather than on the products or services we put into the world. Though it’s true that inclusive design has been around forever, it has taken a center stage in workplace discussions in recent years.

Why now?

The rapid evolution of technology has had a significant impact on society, and these impacts have also been translated into the product development industry. Recent changes in demographics, heightened awareness of social inequities, and the clear mismatches between humans and technology have shifted into the mainstream.

Microsoft explains that “Disability happens at the points of interaction between a person and society. Physical, cognitive, and social exclusion is the result of mismatched interactions.” Also, Kat Holmes – technologist, entrepreneur, and author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design – argues that designed objects reject their users, like not considering left-handed people for day-to day objects. She explains, that “these mismatches are the building blocks of exclusion.” Not only do they prevent users from experiencing them fully as intended, but they also leave an exclusion feeling attached. Further, “an exclusive design places a burden on people to find their own workarounds.”

The elevation of social consciousness has changed the way we approach design. The world continues to grow, yet becomes ‘smaller’ as humans become increasingly connected, thanks to technology. For all these reasons, the audiences we must consider are much more nuanced.

As Microsoft writes, “Every decision we make can raise or lower barriers to participation in society. It’s our collective responsibility to lower these barriers though inclusive products, services, environments, and experiences. (emphasis added)”

The (business) case for diversity and inclusion in design

What a huge opportunity! We can adopt new perspectives and therefore reshape how we want to design and for whom. As designers, we have a key role in what we design, who we consider to be our main user base, and who we inadvertently exclude. By understanding why diversity and inclusive design are important, we contribute not only to creating a more equitable world, but also to helping the businesses we work for expand too.

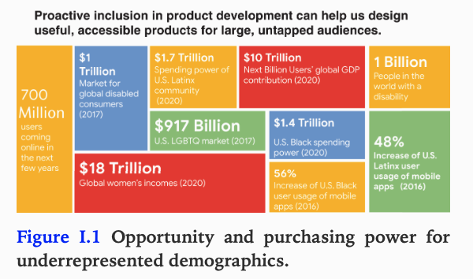

As Annie explains, “many people mistakenly assume that underrepresented users comprise an insignificant portion of the population, so making them a priority is a low priority business decision.” The fact is, the cohort of underrepresented users is vast, and the common misconception leads businesses to often overlook the lost revenue that untapped – i.e., excluded – audiences might bring.

In Building for Everyone, she writes that according to Google estimates, failure to serve these untapped segments of the population will yield a lost growth opportunity in the tens of trillions of dollars. What’s more, Google expects an approximate of 700 million additional users in the next few years, which would mean additional trillions of dollars for potential purchases or product usage.

According to McKinsey’s Delivering through diversity report, “Awareness of the business case for inclusion and diversity is on the rise…. Companies have increasingly begun to regard inclusion and diversity as a source of competitive advantage, and specifically as a key enabler of growth.”

In a more recent report, How Diversity & Inclusion Matter, McKinsey writes, “The shift to technology-enabled remote working presents an opportunity for companies to accelerate building inclusive and agile cultures.”

Moreover, as declared by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), “The market of people with disabilities is large and growing as the global population ages. […] In the U.S., the annual discretionary spending of people with disabilities is over $200 billion.” Therefore, it’s not just Google that might benefit from expanding their market reach through inclusive design.

Non-inclusive design is bad for business

Cambridge’s toolkit argues that “the importance of adopting good, inclusive design principles early in the conceptual design stage is demonstrated by a report from the Design Council (Mynott et al., 1994), which found that changes after release cost 10,000 times more than changes made during conceptual design.” Anyone who works in technology knows this to be true.

We’ve all seen countless projects get repurposed when they had already been implemented, and we understand how much that costs, not only in time and money (redevelopment, relaunch, and research), but also what it does to our end users: friction and user dissatisfaction. Such an experience can be deadly to certain brands, especially if people feel underrepresented and decide to pivot to a competitor.

As the Cambridge report explains, “One costly example of insufficient accommodation of user diversity relates to the U.S. Treasury. A court ruled that the Treasury discriminated against the blind and visually impaired by designing all denominations of currency in the same size and texture.” As a result, the court ordered the Treasury to absorb the cost and distribution of currency reader devices to eligible individuals.

Cambridge’s inclusive design business case materials offers yet another example: “Target Corporation was taken to court by the U.S. National Federation of the Blind over its website’s inaccessibility to blind and visually impaired users. Target settled for damages of USD6 million and attorney’s fees and costs over USD3.7 million. [Target] also had to make its site fully accessible.”

Conclusion

Applying a diverse and inclusive lens when designing products or services is a must. And you don’t need to take my word for it. In addition to this article, there are countless resources, research, and Ted talks that stress the importance of this subject. I’ve shared only a few. But I wanted to conclude with some thoughts:

As designers, developers, and makers, we need to adopt an inclusive mindset, not just because it’s good for business, but also because it’s the path toward building a more equitable society.

The benefits are countless, and there is also a lot to lose (business-wise) if you don’t incorporate it sooner rather than later. It’s important to encourage conversation and create the space to reflect and identify the systems in place that continue to oppress us. Building products in a non-inclusive way is one of them.

I passionately believe that it’s the product builder’s mission to help transform the organizations where we work and the clients whom we serve by initiating these conversations and reflections as to why this is mission critical.

Hope this article inspires someone!

Want to talk about adopting a diverse and inclusive mindset for your team? Contact us! And be sure to check out our Diversity and Inclusion Design Training Guide.

References

Design for All: Why Inclusion Matters in Business – a podcast featuring Kat Holmes

Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design, by Kat Holmes

Building for Everyone, by Annie Jean-Baptiste

Product Inclusion Leadership: Insights from Google SVP Hiroshi Lockheimer, by Annie Jean-Baptiste

McKinsey Report – Diversity wins: How inclusion matters

McKinsey Report – Delivering through diversity

Cambridge Inclusive Design Toolkit

British Standards Institute – Inclusivity standard

Disabled People in the World in 2019: Facts and Figures

Good Design is Inclusive, and Inclusive Design is Good for Everyone; These TED Talks Prove it, by The Carrera Agency/Designing North

Elise Roy Ted Talk – When we design for disability, we all benefit

Learn more about designing for inclusion with the ITX ebook:

Getting Started with Product Inclusion – An imperfect guide to thinking bigger and building better digital experiences.

Nicole Btesh is a User Experience designer and facilitator. She uses contextual research and co-design workshops to create better products and services, and to innovate faster. At ITX, she co-created a framework to adapt in-person workshops to an entirely virtual environment. She also helped create a Diversity and Inclusion baseline training at ITX. She is passionate about design and gender studies and hosted Spain’s first-ever Gender Design Service Jam.